|

Why is live electronic viewing such an issue? The simplest digital point-and-shoot models all have it (and nothing else), why not SLRs?

There are a number of reasons, ant the foremost is the same mirror which makes optical through-the-lens viewing possible. Until the shutter is released, the mirror stays in the "down" position, redirecting the light towards the viewing screen, and creating the real (as opposed to aerial) image on it, to be viewed through a magnifying eyepiece. (The pentaprism, allowing for eye-level viewing of non-inverted image is a nice extra, first introduced in the German Contax S back in 1949.) Obviously, the image sensor, hidden behind the mirror, gets no light, therefore no preview.

The E-10 used a smart trick to bypass this limitation. Instead of a swinging mirror, it had a fixed, semi-transparent one (more exactly, a prism beam-splitter), letting some of the light through to the sensor, while redirecting some to the viewing screen. The idea was used back in 1970, by Canon in their Pellix SLR, allowing for quieter operation and faster frame rate, but it was never adopted in another camera.

Nothing comes free. The sensor gets less light (read: lower ISO rating), and so does the viewfinder. Still, the finder in the E-10/E-20 is surprisingly bright: brighter than in all Olympus digital SLRs, in addition to being larger. This was achieved by using a semi-transparent screen (instead of a "real" groundglass), a trick used for at least 50 years in interchangeable SLR screens for macro- and microphotography. There is another catch, however: the viewed image becomes partly (or mostly) aerial, what means that our eye may see it sharp even if it is not exactly in the screen plane. Here goes the focusing (manual at least), and some users will not have that.

A less obvious problem with live preview is that most of upper-end digital image sensors are not well-suited to prolonged exposures to intense light. In the best case they need to be "flushed" (with shutter closed) just before the actual exposure; this causes an extra delay before the shutter release is pressed and the picture taken. The sequence is quite long: the shutter is open for viewing, metering, and autofocus; then it is closed and the sensor is flushed; then it opens again to start the exposure, and closes to end it; then the image is collected from the sensor (and this takes some time); finally the shutter opens again to allow for viewing.

Still, I was quietly expecting that someone (Olympus or not) will revive the concept of the E-10/E-20 by adding lens interchangeability. Was I for a surprise!

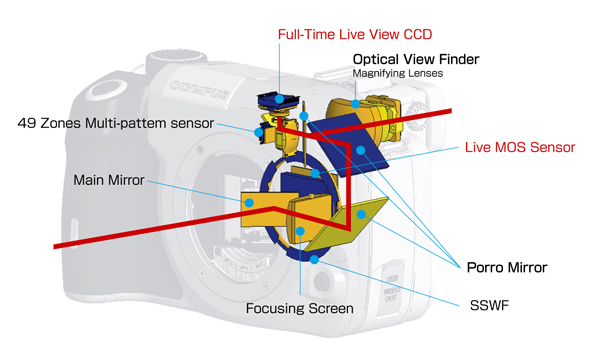

Here comes the E-330. The camera looks very much like the older E-300, with the flat-top design (no pentaprism or pentamirror hump), and the funky, side-swinging mirror. This unorthodox design has an advantage in this case, allowing for longer optical path between the screen (which must be as close to the mirror as the image sensor is) and the eyepiece. And it is between these two, where the Olympus' new trick springs into action. Here is a drawing courtesy by Olympus which may be helpful in the explanation.

|

|

In addition to the "main" mirror, three others are used to redirect the screen image to the eyepiece — exactly like in the E-300 (a solution referred to as a "straight-line reverser", one of the two most common types). The difference is that the last one of those three (seen from this angle as just a vertical line) is semi-transparent. It reflects most of the screen image light towards the eyepiece, but lets some through — to another, second image sensor, whose sole purpose is to provide live electronic preview.

This, actually, requires another lens system to create on the viewing imager a projected, real image of the real image [sic!] from the focusing screen. This system is located beyond yet another, fifth, mirror, used to change the light direction again, as the viewing sensor is pointing down, but this is not so important. To complicate things further, that mirror is also semi-transparent, letting some light towards a metering array.

The "viewing" sensor is actually a full-fledged CCD chip, the some one as used in the new Stylus (Digital Mju) 810 model by Olympus. It is not really getting much light (the optical finder gets most, and some goes to the metering matrix), so it is working in a special mode where the output from a 3x3 array of pixels is merged into one "fat" pixel. This makes its effective resolution slightly below 1 MP, still plenty for preview purposes.

Indeed, all is done with mirrors. There is a sixth one, not shown in the drawing, and not important for this discussion, but you may still want to know. It is hinged piggyback on the back side of the main mirror (i.e., the first one behind the lens), and its purpose is to redirect some of the light towards the autofocus sensors. What light? Oh, did I mention that parts of the main mirror are semi-transparent to allow for that? (A common solution in AF SLRs, not unique to the E-330.)

The bottom line is that the user gets a full-time, electronic preview, although not from the same sensor which is used to record the image. But this is not the end of it. The E-330 does this not just as described above, but in two different ways!

The number of mirrors and lens elements involved in the procedure calls for very strict mechanical and optical tolerances. One may suspect that this full-time preview is OK for casual use (framing shots from waist level of overhead), but not much more, and this is the rationale for the other preview mode.

The process described above is referred to as "Mode A". In "Mode B" the goal is reached in a different way. Here the main mirror goes up for electronic viewing (disabling the optical finder), the shutter opens, and the live preview uses the signal from the main imager, very much like in the E-10, including the double close/open shutter sequence described in the discussion of the that camera (except that this is a focal-plane shutter). An advantage of this mode is that the preview, using the signal from the actual imager, can be greatly magnified for critical focusing (manual only: the piggyback mirror is out of the way together with the main one). Obviously, Mode B is most buseful in tripod work.

Another complication: Kodak imagers used in previous E-System cameras (E-1, E-300, E-500) provide excellent results, but are not suitable for continuous use. Therefore Olympus, in an abrupt turn, switched to a CMOS chip (by Panasonic?), more suitable for this mixed use. How this will affect the image quality remains to be seen.

As impressed as I am by this ambitious attempt by Olympus to move the technology further, I am also a bit skeptical. This is quite an elaborate scheme, introducing a lot of extra complexity of mechanical, optical, and electronic nature. Whether this expense is justified to provide the live preview, and how it may impact the reliability of the whole, remains to be seen. I am not so sure. Usually simpler works better (unless it is not enough).

Still, with the more conventional (and very well-performing) E-500 being made along with the new E-330, Olympus seems to be playing it safe, catering both to conservatives like myself, and to those who yearn to be different. Whether the new model will prove to be a star, or a dud (and only time will tell), this is not a "yet another SLR".

|